Table of Contents

Parent: JesusWordsOnly

Did John's Epistles Identify Paul As A False Prophet

Introduction

John's First and Second Epistle talk in words reminiscent of (Rev. 2:2). John speaks in his first epistle about testing those who claim to have come from God. John says you can find them to be false prophets. John writes:

Dear friends, don't believe everyone who claims to have the Spirit

of God. Test them all to find out if they really do come from

God. Many false prophets have already gone out into the world

(1John 4:1) CEV.

In John's epistles, John thereafter gives us several tests that his readers can use to know whether some alleged prophet comes from God.

His spirit [does not] say that Jesus Christ had truly human flesh

(sarx , flesh). (1John 4:2).

We belong to God, and everyone who knows God will listen to us

[i.e., the twelve apostles]. But the people who don't know God

won't listen to us. That is how we can tell the Spirit that speaks

the truth from the one that tells lies. (1John 4:6) CEV.

These people came from our own group, yet they were not part of

us. If they had been part of us, they would have stayed with

us. But they left, transgresses [i.e., goes beyond] and doesn't

remain in the teachings of Christ, doesn't have God [i.e., breaks

fellowship with God]. He who remains in the teachings [of Jesus

Christ], the same has both the Father and the Son. (2John 1:9)

Websters.

Thus, John gives us several criteria to identify the false prophets even if they "claim to have the Spirit" of God:

-

They teach a heresy that Jesus did not come in truly human flesh (i.e., his flesh just appeared to be human flesh); or

-

They do not listen to the twelve apostles; or

-

They became a part of the apostles' group but left the apostles' group; or

-

They do not remain in the teachings by the twelve of what Jesus taught.

As hard as it may be to believe, each of these four points in First and Second John apply to Paul.

Did Paul Refuse to Listen to the Apostles?

First, Paul did not listen to the twelve apostles. Paul rails in (Gal. 2:1-9) at the three "so-called" apostolic pillars of the Jerusalem church (including John) (Gal. 2:9). Paul says again they were "reputed to be something" (Gal. 2:2,6), but "whatsoever they were it makes no difference to me; God does not accept a man's person [i.e., judge by their position and rank]." (Gal. 2:6). Paul then expressly declares that he received nothing from the twelve apostles.

I say [those] who were of repute [i.e., the apostles in context]

imparted nothing to me, learning anything about Jesus from the

apostles or the reputed pillars of the church - Peter, John, and James.

Now listen again to what John - one of the three mentioned by Paul as "seeming pillars" - had to say about this kind of behavior. John writes:

We belong to God, and everyone who knows God will listen to us

[i.e., the twelve apostles].

But the people who don't know God won't listen to us. That is how

we can tell the Spirit that speaks the truth from the one that

tells lies. (1John 4:6) CEV

John clearly would regard someone such as Paul who refused to learn from the twelve as someone who does not "know God." The fact Paul would not listen to the twelve (and was proud of it) allows us to realize Paul is one who "tells lies," if we accept John's direction.

Paul's Admission of Parting Ways With the Apostles

Paul also fits (1John 2:19) because he left their group. Paul admits this. However, Paul claims it was because the twelve apostles decided they would alone focus on Jews and Paul alone we should go unto the Gentiles, and they "unto the circumcision";

Does Paul's account, any way you mull it over, make sense? Not only are there issues of plausibility, but, if Paul is telling the truth, it means the twelve apostles were willing to violate the Holy Spirit's guidance to the twelve that Peter was the Apostle to the Gentiles, as is clearly stated in (Acts 15:7).

God Already Appointed Peter the Apostle to the Gentiles

The Holy Spirit had already showed the twelve that Peter (not Paul) was the Apostle to the Gentiles. At the Jerusalem Council, with Paul among those at his feet, Peter gets up and says he is the Apostle to the Gentiles in (Acts 15:7):

And when there had been much disputing,

Peter rose up, and said unto them, Men and brethren, ye know how

that a good while ago God mode choice among us, that the Gentiles

by my mouth should hear the word of the gospel, [i.e., Peter and

the Jerusalem leaders] unto the circumcision [i.e., Jews]."

What Paul claims happened makes no sense. If it happened by mutual agreement, then you would have to conclude Peter believed God changed his mind about Peter's role. This would require Peter to disregard God's choice a "good while ago" mentioned in Acts 15:7 that he be the Apostle to the Gentiles. This is completely implausible.

Thus, to believe Paul, you have to believe God would change His mind who was to go to the Gentiles. Yet, for what purpose? Wouldn't two be better than one? Why would God cut out Peter entirely ?

Furthermore, why would Peter diminish this Gentile ministry among the twelve that he initiated with Cornelius? Why would he put Paul alone as the leader to convert Gentiles? Moreover, there were Gentiles right in Jerusalem. How could the apostles sensibly divide up their mission field on the basis of Gentile and Jew?

The answer to all these paradoxes is quite obvious. Paul is putting a good spin on a division between himself and the home church. By claiming in a letter to Gentiles that he was still authorized to evangelize to them, they would believe him. They could not phone Jerusalem to find out the truth. Now listen to John's evaluation of what this really meant:

These people came from our own group, yet they were not part of

us. If they had been part of us, they would have stayed with

us. But they left, possibly apply to Paul. What most Christians

would not concede as possible is that Paul also taught Jesus did

not have truly human flesh.

Before we address this point, let's distinguish this next point from what has preceded. This 'human flesh' issue is a completely independent ground to evaluate Paul. John could be talking about Paul on the issue of leaving their group (1 John 2:19) and not listening to the twelve (1John 4:6), but not be addressing Paul on the 'human flesh issue' in (1 John 4:2). One point does not necessarily have anything to do with the other.

That said, let's investigate whether this issue of 'human flesh' in 1 John 4:2 applies to Paul as well.

To understand what teaching John is opposing when he faults as deceivers those who say "Jesus did not have human flesh," one must have a little schooling in church history. We today assume John is talking about people who say Jesus came in an imaginary way. This is not John's meaning.

The heresy that John is referring to is the claim Jesus did not have truly human flesh. Marcion's doctrine is an example of this viewpoint. Marcion came on the scene of history in approximately 144 A.D. John's epistle is written earlier, and thus is not actually directed at Marcion. Marcion helps us, however, to identify the precursor heresy that John is attacking. Marcion's doctrines are well-known. Marcion taught salvation by faith alone, the Law of Moses was abrogated, and he insisted Paul alone had the true Gospel, to the exclusion of the twelve apostles. (See Appendix B: How the Canon Was Formed 3.8 JWO/JWO_20_01_HowTheCanonWasFormed_0112.)

Marcion was not denying Jesus came and looked like a man. Rather, Marcion was claiming that Jesus' flesh could not be human in our sense. Why? What did Marcion mean?

Marcion was a devout Paulunist, as mentioned before. Paul taught the doctrine that all human flesh inherits the original sin of Adam. (Rom. 5:0). If Jesus truly had human flesh, Marcion must have been concerned that Jesus would have come in a human flesh which Paul taught was inherently sinful due to the taint of original sin. Incidentally, Paul's ideas on human flesh being inherently sinful was contrary to Hebrew Scriptures which taught all flesh was clean unless some practice or conduct made it unclean. (See, e.g.. (Lev. 15:2) et seq .) In light of Paul's new doctrine, Marcion wanted to protect Jesus from being regarded as inherently sinful. Thus, Marcion was denying Jesus had truly human flesh.

Marcion's teaching on Jesus' flesh is known by scholars as docetism. The word docetism comes from a Greek work that means appear. Docetism says Jesus only appeared to come in human flesh. Docetism also became popular later among Gnostics who taught salvation by knowledge and mysteries. (Marcion taught salvation by faith in Jesus, so he is not Gnostic in the true sense.) The Gnostics were never the threat to Christianity that the Marcionites represented. Gnostics were simply writers who had no churches. The Marcionites, on the other hand, were successful in establishing a competing Paul-oriented Christian church system in most major cities that rivaled the churches founded by the twelve apostles. The Marcionites had church buildings, clergy, regular services, etc.

It was in this context that John's letter from the 90s A.D., in particular (1John 4:2), must be understood as condemning docetism. ?

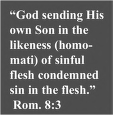

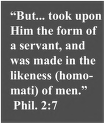

Yes. Heretical docetism is found expressly in Paul. For Paul writes Jesus only appeared to be a man and to come in sinful human flesh. (Rom. 8:3) "likeness" or "appearance" of "sinful human flesh;" 1 see also (Phil. 2:7) "appeared to be a man".)

Specialists in ancient Greek who are Christian struggle to find no heresy in Paul's words in both passages. Vincent is one of the leading Christian scholars who has done a Greek language commentary on the entire New Testament. Here is how Vincent's Word Studies tries to fashion an escape from Paul uttering heresy. First, Vincent explains Paul liter

"God sending His own Son in the likeness (homomati) of sinful

flesh condemned sin in the flesh." (Rom. 8:3)

- In (Rom. 8:3), Paul writes: "For what the law could not do, in that it was weak through the flesh, God, sending his own Son in the likeness [i.e., appearance] of sinful flesh and for sin, condemned sin in the flesh." (ASV)

- Of course, like Marcion, Paul does not dispute that Jesus was the Godhead who appeared in a "body" ( somatikos ). (Col. 2:9). A body does not imply human flesh. Yet, Robertson believes that Col. 2:9 disposes with the docetic theory. Yet, Robertson describes this theory as "Jesus had no human body." This is not a precise description, at least of Marcion's docetism. Rather, docetism says the body in which Jesus lived lacked human flesh. It just appeared to be human flesh. Robertson's analysis thus lacks precise focus on what is ally says in (Rom. 8:3) that Jesus came in the likeness of the flesh of sin. Vincent then says had Paul not used the word likeness, Paul would be saying Jesus had come in "the sin of flesh f which "would [then] have represented Him as partaking of sin." Thus, Vincent says Paul does not deny Jesus came in the flesh ( i.e Paul is not denying Jesus' humanity), but rather Paul insists that Jesus came only in the likeness of sinful flesh.

My answer to Vincent is simple: you have proved my case. Vincent is conceding the Greek word homomati (which translates as likeness) means Jesus did not truly come in the flesh of sin. Vincent is intentionally ignoring what this means in Paul's theology. To Paul, all flesh is sinful. There is no such thing as flesh that is holy in Paul's outlook. For Paul, you are either in the Spirit or in the flesh. The latter he equates with sin. (Gal. 5:5,16-20.) So Paul is saying Jesus only appeared to come in sinful human flesh. In Paul's theology of original sin (Rom. eh. 5), this is the same thing as saying Jesus did not come in truly human flesh. It only appeared to be human (sinful) flesh. Paul was completely docetic. That is how Marcion formed his doctrine: straight from Paul.

Furthermore, when you compare (Rom. 8:3) to (Phil. 2:7), there is no mistaking Paul's viewpoint. In Philippians 2:7, Paul this time says Jesus came in the "likeness (homomati) of men," not flesh of sin. Following Vincent's previous agreement on homomatf s meaning, this verse says Jesus did not truly come as a man. He just appeared as if he was a man. Vincent again struggles desperately to offer an interpretation of Philippians 2:7 that avoids Paul being a heretic. Vincent ends up conceding " likeness of men expresses the fact that His Mode of manifestation resembled what men are." When you strip away Vincent's vague words, Vincent concedes Paul teaches Jesus only appeared to be a man. Thus, he was not truly a man. This means Paul was 100% flesh). (1John 4:2.)

Was Marcion really that far from Paul? As Tertullian summarized Marcion's view, we hear the clear echo of Paul. Marcion taught Jesus "was not what he appeared to be...[saying He was] flesh and yet not flesh, man and not yet man...." (Tertullian, On Marcion, 3.8.)

John s Epistles Are Aimed At A False Teacher Once at Ephesus

The likelihood that John's epistles are veiled ways of talking about Paul gets stronger when we look at other characteristics of the heretic John is identifying in his first two epistles. Historians acknowledge that John's epistles are written of events "almost certainly in Asia Minor in or near Ephesus. John's concern, Ivor Davidson continues, was about someone in that region who said Jesus was "not truly a flesh-and-blood human being." To counter him, John also later wrote in his Gospel that the Word "became flesh" (John 1:14.)

Who could John be concerned about who taught docetism in that region of Ephesus? Again the answer is obviously Paul. For it was Paul who wrote in (Rom. 8:3) and (Phil. 2:7) that Jesus only appeared to come as a man and in sinful human flesh. Paul must have carried the same message with himself to Ephesus. John's focus in his epistles is obviously on the same person of whom (Rev. 2:2) is identifying was "a liar" to the Ephesians. John has the same person in mind in the same city of Ephesus. John's intended object must be Paul.

-

Ivor J. Davidson, The Birth of the Church: From Jesus to Constantine A.D. 30-312

-

This and other evidence led Christian scholar Charles M. Nielsen to argue that Papias was writing "against a growing 'Paulinis' [i.e. Paulinism] in Asia Minor circa 125-135 A.D., just prior to full blown Marcionism [i. e ., Paul-onlyism]."

5 Nielsen contends Papias' opponent was Polycarp, bishop of Smyrna, who favored Paul. (We have more to say on Polycarp in a moment.)

Thus, in Papias-a bishop of the early church and close associate of Apostle John-we find a figure who already is fighting a growing Paulinism in pre-Marcion times. This allows an inference that Apostle John shared the same concern about Paul that we identify in John's letters. Apostle John then passed on his concern to Papias. This led Papias to fight the "growing Paulinis" (i.e., Paulinism) in Asia Minor - the region to which Ephesus belonged.

-

"Papias," The Catholic Encyclopedia.

-

Rev. (Lutheran) D. Richard Stuckwisch "Saint Polycarp of Smyrna: Johannine or Pauline Figure?" Concordia Theological Quarterly (January-April 1997)Vol. 61 at 113, 118, citing Charles M. Nielsen, "Papias: Polemicist Against Whom?" Theological Studies 35 (September 1974): 529-535; Charles Nielsen "Polycarp and Marcion: A Note," Theological Studies 47 (June 1986): 297-399; Charles Nielsen, "Polycarp, Paul and the Scriptures," Anglican Theological Review negatively about Paul, as I contend above, then why does Polycarp have such high praise for Paul?

It is a good question. However, it turns out that Polycarp did not likely know Apostle John. Thus, the question becomes irrelevant. It rests on a faulty assumption that Polycarp knew Apostle John.

How did we arrive at the commonly heard notion that Polycarp was associated with Apostle John? It comes solely from Ireneaus and those quoting Ireneaus such as Tertullian. However, there is strong reason to doubt Irenaeus' claim.

Irenaeus wrote of a childhood memory listening to Polycarp tell of his familiarity with Apostle John. However, none of the surviving writings of Polycarp make any mention of his association with Apostle John. Nor is such an association mentioned in the two biographical earlier accounts of Polycarp contained in Life of Polycarp and The Constitution of the Apostles. Yet, these biographies predate Irenaeus and thus were closer in time to Polycarp's life. Likewise, Polycarp's own writings show no knowledge of John's Gospel. This seems extraordinarily unlikely had John been his associate late in life. As a result of the cumulative weight of evidence, most Christian scholars (including conservative ones) agree that Ireneaus' childhood memory misunderstood something Polycarp said. Perhaps Polycarp was talking of a familiarity with John the Elder rather than Apostle John. or after John's epistles. Thus, even if there were some association between John and Polycarp, we cannot be sure whether Polycarp's positive view of Paul continued after that association began.

Accordingly, there is no clear case that someone associated with John after he wrote his epistles had a positive opinion of Paul. To the contrary, the only person whom we confidently can conclude knew John in this time period- Papias-was engaged in resistance to rising Paulinism, according to Christian scholars.

Thus, John's letters appear to reveal even more clearly who was being spoken about in (Rev. 2:2). John's true friends (i.e., Papias) had the same negative outlook on Paulinism at that time.

Chapter 13 Conclusion

Accordingly, when John's epistles tell us the four characteristics of a false prophet and teacher who left associating with the twelve apostles, they fit Paul like a glove. Scholars agree that John is identifying a false teacher who once had been at Ephesus who taught Jesus did not come in truly human flesh. This too fits Paul like a glove. Paul expressly taught Jesus did not come in human flesh-it only appeared that way. John in his epistle is thus pointing precisely at Paul without using Paul's name.

John, in effect, tells us in (1John 4:2-3) to regard Paul as uninspired and a liar, no matter how appealing Paul's theological arguments may sound.

-

Rev. (Lutheran) D. Richard Stuckwisch "Saint Polycarp of Smyrna: Johannine or Pauline Figure?" Concordia Theological Quarterly (January-April 1997) Vol. 61 at 113 et secy exclusive Against Marcion

"I must with the best of reasons approach this inquiry with uneasiness when I find one affirmed to be an apostle, of whom in the list of the apostles in the gospel I find no trace.... Let's put in evidence all the documents that attest his apostleship. He [i.e., Paul] himself says Marcion, claims to be an apostle, and that not from men nor through any man, but through Jesus Christ. Clearly any man can make claims for himself: but his claim is confirmed by another person's attestation. One person writes the document, another signs it, a third attests the signature, and a fourth enters it in the records. No man is for himself both claimant and witness." (See Tertullian, Against Marcion (207 A.D.) quoted at 418-19